Oct

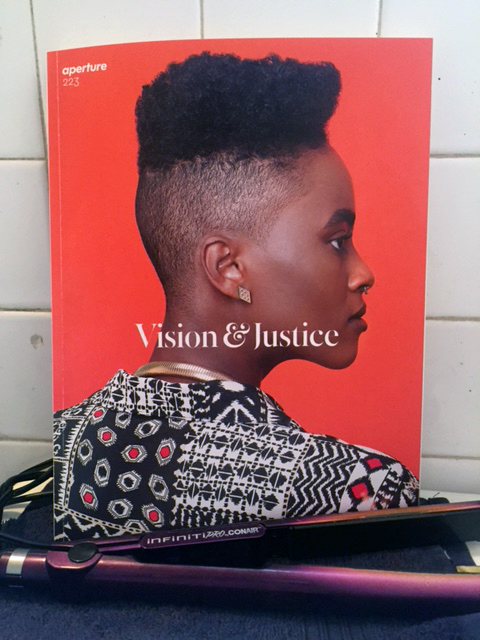

Reading in the Bathroom | Aperture #223, Vision and Justice

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

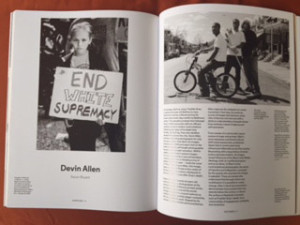

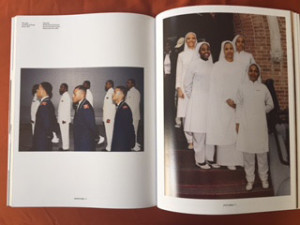

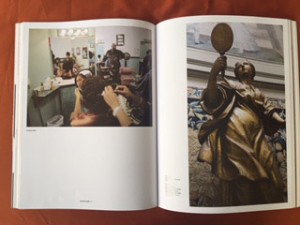

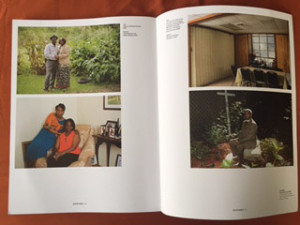

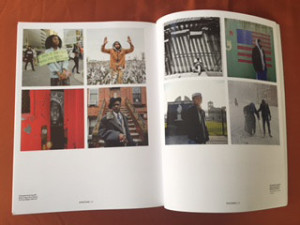

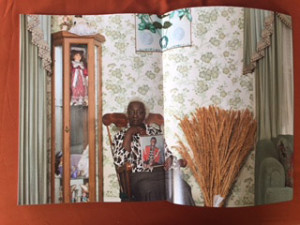

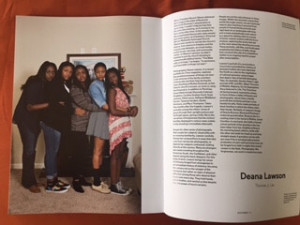

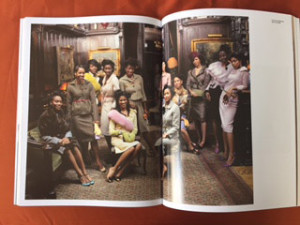

Aperture, a “not-for-profit foundation, connects the photo community and its audiences with the most inspiring work, the sharpest ideas, and with each other — in print, in person, and online.” For the first time in its history, the quarterly exclusively focused on black visual narratives. Vision & Justice edited by Michael Famighetti and guest edited by Sarah Lewis, the magazine features interviews with Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young. Cultural critiques and essays about artists like Toyin Ojih Odutola and Lorna Simpson are written by Claudia Rankine and Margo Jefferson, respectfully. Familiar images from photographer Annie Leibovitz showcase Michelle and Barack Obama, Susan Rice, and Serena Williams dot the half-way mark. The second half is dedicated to editorial depictions of everyday people, but more on that later.

”My life is also colored by friends who wore ornate hairstyles for hair shows, featuring hair colors not found in nature. Finger waves dusted with glitter, and rows of tight curling iron curls. and Black men who diligently brushed Ceasar waves. Men and women who hung out the side of candy-painted Cadillacs and custom cars … Those people seem to be curiously missing from this issue.

Black Empowerment is Necessary to Survive, But Thriving is Better

My sympathies for this quarterly are deeply personal. My black childhood is colored by photos of black men near my crib. Prideful images of black people with gorgeous African features decorated our home. I played exclusively with black dolls, bought by my mother. My middle name Nehanda, is inspired by the woman who inspired the revolt against the colonization of Mashonaland. Growing up in a racially regressive city like Milwaukee required these reinforcements. So I get why certain visuals of blackness are important for self-actualization, identity, and self-empowerment.

My life is also colored by friends who wore ornate hairstyles for hair shows, featuring hair colors not found in nature. Finger waves dusted with glitter, and rows of tight curling iron curls. Black men who diligently brushed Ceasar waves. Men and women who hung out the side of candy-painted Cadillacs and custom cars. My favorite 90s R&B girl group who wore nails that defy comprehension. People who turned camouflage into a vibrant fashion choice. People who twerked, bounced, and perc’d in school hallways, barbecues, parties, and nightclubs. People who rebelliously wore their pants low, because they or someone they knew had been in jail. Men and women who loved each other, heterosexually or homosexually. People who are socially conservative and people who are liberal socialists.

Those people seem to be curiously missing from this issue.

Sarah Lewis writes in her opening letter that,

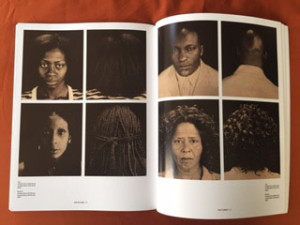

No matter the topic — beauty, family, politics, power — the quest for a legacy of photographic representation of African Americans has been about these two things. The centuries-long effort to craft an image to pay honor to the full humanity of black life is a corrective task for which photography and cinema have been central, even indispensable.

Lewis’ intentions seem sincere, and I couldn’t agree more. But there is a contradiction between what was intended and what is represented. Anyone outside the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, or Chicagoland area, anyone with a weave, a relaxer, gold teeth, pants hanging low, clear heels, cornrows, finger waves, curling iron rows, a Republican, anyone openly LGBT, and anyone with a physical disability seem to be missing from Aperture‘s Vision & Justice. Anyone with a weight problem doesn’t appear until pg. 142 in a 152-page quarterly.

Even with good intentions, certain people in Vision & Justice are not acknowledged as prideful. Maybe they were sifted out of the editorial process or our cultural imaginations due to time. Maybe they don’t adhere to our carefully cultivated sense of what we believe is prideful. The results mean some people are left out of who has contributed to the collective work and responsibility of achieving justice through good citizenship and civic duty, social activism and self-advocacy, generational rebelliousness, differing political ideologies, self-adornment, and self-expression.

Video: Joan Morgan on Pleasure, Black Women, and Being Creative

The Power of Specific Black Images Associated with Black Pride

”The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see. ― James Baldwin

As much as I love iconic images of black pride, there are political consequences for building black iconography around politically or historically limited images. An article on The Atlantic, “Being Black — but Not Too Black in the Workplace” cite legal scholars Mitu Gulati and Devon Carbado. In their book Working Identity:

Carbado and Gulati also note that minority professionals tread cautiously to avoid upsetting the majority group’s sensibilities. Put simply, they can be visibly black, but don’t want to be perceived as stereotypically black. As Carbado and Gulati write, a black female candidate for a law firm who chemically straightens her hair, is in a nuclear family structure, and resides in a predominantly white neighborhood signals a fealty to (often unspoken) racial norms. She does so in a way that an equally qualified black woman candidate who wears dreadlocks, has a history of pushing for racial change in the legal field, is a single mother, and lives in the inner city does not.

These findings reveal a rather pernicious perception of (in this case) black women as first seen, then heard when it comes to being qualified for professional work, political outspokenness or retreat. These assumptions put black women specifically in a bind in which they cannot perform the work of social justice, self-empowerment, and self-expression without adhering to what they should look like, first. This manifests itself in Amber Rose being dismissed when discussing slut shaming, U.S. Representative Mia Love (R-UT) mocked for her braids, or the mere fascination that it’s shockingly possible our First Lady can go from relaxed to natural. We as artists, designers, photographers, and illustrators have real power and responsibility here. When we idealize only a few images of black power, it is made harder for others to do the actual work of being seen as powerful.

”Do we all have full autonomy over our bodies as a source of self-adornment, rebellion, and expression? Can we all occupy spaces of protest, discourse, and political action, without a value placed on who we love and what we've done to our own bodies?

The back half (above) dedicates itself to images of everyday black life, black life in peril, protest, or in mourning. This part is frankly rather depressing. While I agree with my colleague, that love is not ALL we need, there has to be room for understanding our pleasure if we are to thrive.

Blackness is Vast, Like the Universe. And Black Creatives Can Further Expand It

I’m not here to spitball. I think a project like Vision & Justice has potential. AIGA Medalist Emory Douglas talks about what it means to be a revolutionary artist.

Artists have a way of instantly communicating essence …Things are made clear, almost like a language, and so art is a powerful tool to communicate with the community.

Blackness is like the universe. It is beautiful in its vastness, therefore capturing it all is sort of like being an astrophysicist. So I wonder if this issue would have benefitted from a collection of guest editors, rather than one. Photographer and former photo editor for The Fader (2003-2007) Dorothy Hong would’ve helped. Editor-in-Chief Suzanne Boyd and Art Director Erika Perry — the team behind the short-lived but legendary Suede Magazine — would’ve also added additional layers to the black experience.

For some, their black cultural awakening might have been the first time they heard John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, or the first time they saw The Cosby Show. For me, it was the first time I listened to Outkast’s Aquemini, Prince’s Purple Rain, saw the illustrations of Pedro Bell, or the first time I watched Black Orpheus. Those experiences gave me a fictive kinship I did not know I had inside of me until I knew they existed.

The images, interviews, essays, and photos within Vision & Justice are beautiful. However, I would’ve loved to see the following beautiful black people included. I chose well-known people because I don’t want to show a non-public figure without their permission. I’ll admit that I am showing my age with many of these examples. And more than a few of these folks I personally dislike. But our contemporary visual language of the last 20 years has been brightened more my these people.

We are All Free, When Everyone is Free

”Freedom is not something that anybody can be given. Freedom is something people take, and people are as free as they want to be” ― James Baldwin

I say this because the roots of this are about autonomy. Do we all have full autonomy over our bodies as a source of self-adornment, rebellion, and expression? Can we all occupy spaces of protest, discourse, and political action, without a value placed on who we love and what we’ve done to our own bodies?

I do not believe the editors of Aperture #223 Vision & Justice are outright ashamed of anyone. But a big part of how I identify my blackness is left out, and I imagine that may be the case for others. These editorial decisions do not get made in a vacuum. They are made within a socio-political context of cultivated black imagery that tells us what we should be proud of. I ask fellow artists, designers, photographers, and tastemakers — black and nonblack — to include in their imaginations, who is doing the work of seeking justice and being pridefully black.

Reading in the Bathroom is a book review series by IDSL. Reading is obviously not done in the bathroom exclusively. Sometimes it’s at a park bench, outdoor cafe, or on the train. But the best reading is done in the bathroom.