Aug

Implementing The Elusive In-House Creative Brief

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

I have a confession. I haven’t written a creative brief in years.

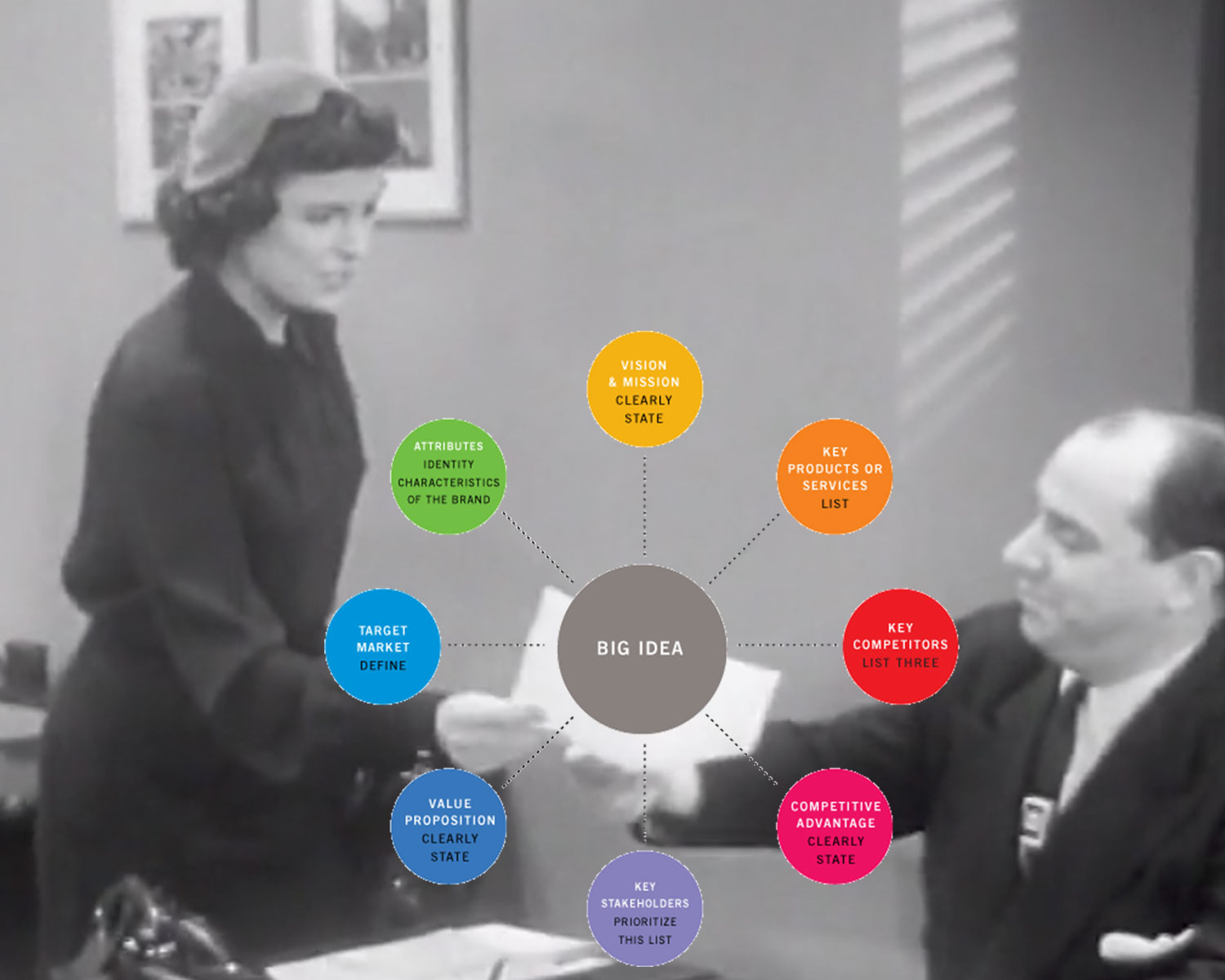

For those who don’t know, a creative brief is a document that declares the goals and intent of a design project. It provides, among many things: the name and profile of the client, their objectives, roles of your creative team, projected timeline, and budget. This tool is often used by design studios and advertising agencies. A creative brief is extremely important, because it acts as a guiding light for a project. It sets up expectations, commitments, and can change as the project changes.

Until I started working on my own personal projects, I haven’t written (or read) one since college. Because for the majority of my career, I’ve worked as an in-house designer.

I started as a junior designer at CBRE a global commercial real estate firm, where outside of a few requests, design was paint-by-numbers. Soon afterward, I worked at Dentons (formerly Mckenna, Long & Aldridge LLP), a law firm that only moved design in-house to save money. And until I created one The Education Trust never had a graphic style guide, let alone a standard creative brief.

”There's no value in writing a brief only you will read.

Part of what makes working in-house so isolating is admitting things like this. It’s kind of an embarrassing admission, and you don’t know if others have the same issue. AIGA’s In-House INitiative aims to supports in-house designers, which now make up the majority of its members. The initiative is great for sharing experiences. But this question of how to implement a creative brief for in-house designers is tricky because not all in-house teams have this problem. And no two in-house design divisions are alike.

There is, however, a problem.

In-house designers are not hired by people who necessarily know or care about the graphic design process. They just want someone to make their work look good (and hopefully save money). That might seem like a good thing, initially. But after awhile your clients/co-workers will see how talented you really are, and want you to produce more ambitious work. How do you start implementing parts of the design process — research, budgets, objectives — that Sue from accounting, Jeff from IT, Kara from communications, or Sarah from editorial have never seen from you before? How do you write a brief for a company that only used you to make their business cards? How do you begin to show the value of a creative brief when your company wants you to head their experience design, and they don’t even know what that is?

”I have a confession. I haven't written a creative brief in years.

These questions cannot simply be answered with a glib, just write the damn brief. After all, if one can introduce a graphic style guide to an education nonprofit, a creative brief can be implemented as well, right? But style guides function differently than briefs. Style guides cover the visual identity system, and unlike a brief, are not project-specific. Plus, a style guide only needs to be maintained every 1-2 years, almost exclusively at the discretion of the design team. Whereas a brief changes as new discoveries are found, and requires regular input from the client. In this case, your co-workers.

For a creative brief to be successful in an in-house environment, you have to get more than a few people on your side to know that it’s worthwhile. There’s no value in writing a brief only you will read. The answers often lie in managing office politics, and massaging the nuances. You won’t call it a creative brief, but simply an email reminding people of the goals. You won’t call it budget management, but simply finding a more affordable vendor. You won’t call it defining the company brand, but you will articulate it back to them throughout the process. Most of this is informal and rarely written down. It keeps the engines going, and doesn’t hurt anyone else’s process.

But it’s not sustainable.

With no formal written design objective(s), you won’t be able to clarify how your solution solved a visual communication problem. With no sense of budget, you don’t know if your time has been under- or over-utilized on the wrong tasks. With no clearly-named team members at the beginning, no one knows who’s responsible for leading meetings or gathering resources. And when the project is over, without a brief there is no reference point for reflection.

”You won't call it a creative brief, but simply an email reminding people of the goals. ...But it's not sustainable.

Design is not a solo sport, but a team effort. When a company hires a designer to be a part of that team, the designer must also have expectations their team can support the process. It’s also the AIGA In-House INitiative’s responsibility to help struggling in-house designers cross the bridge between saying how to write a brief, and having their teams actually use it.

Image courtesy of Internet Archive and @issue Journal.