Jun

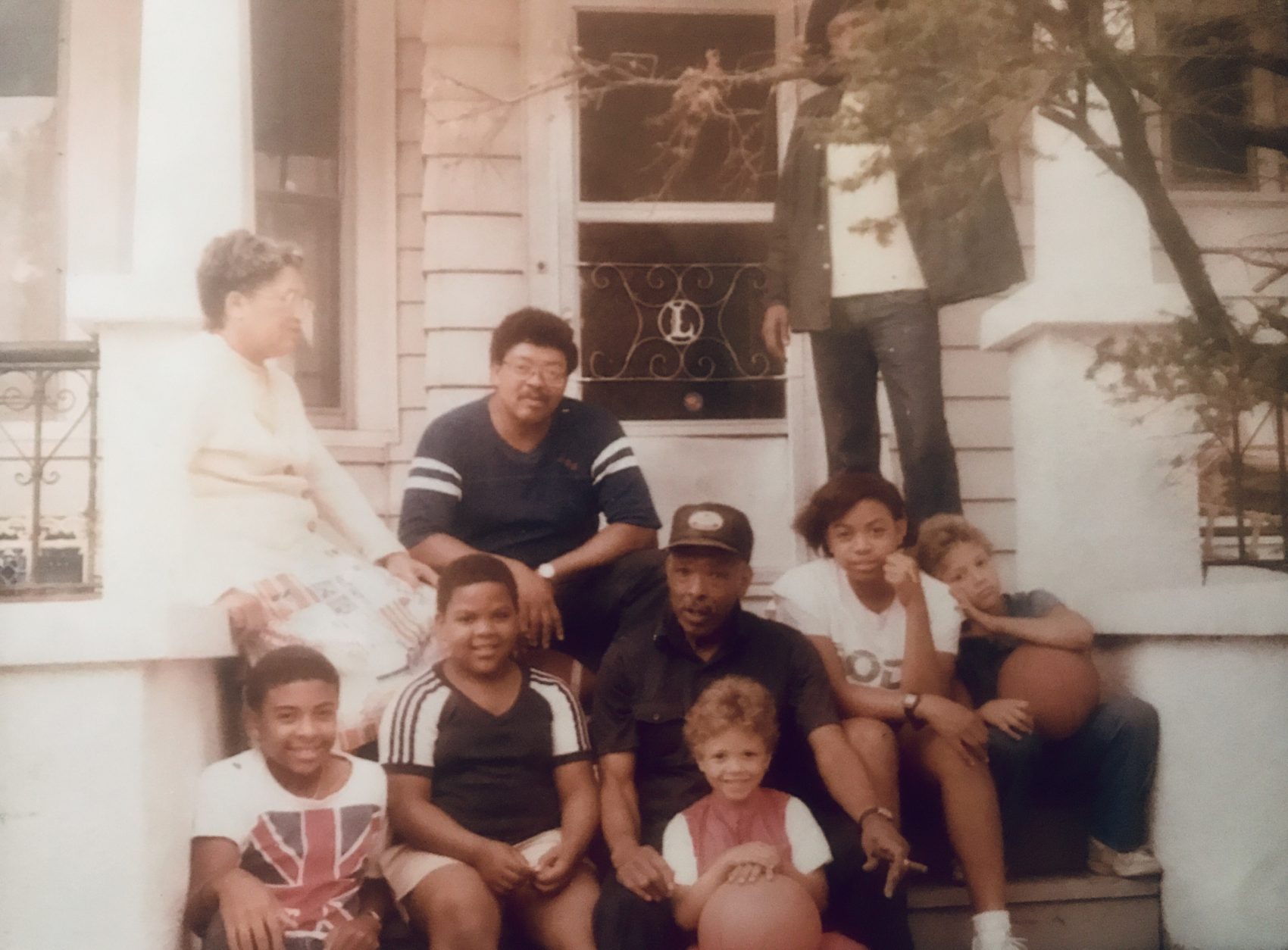

Cultivating Joy, By Design: An Homage to My Brilliant Black Family

How do we make space to care for ourselves?

My grandfather was a truck driver. He came up from rural Alabama and started his family in Milwaukee, WI. Along the way, he became the City of Milwaukee’s first Black sanitation worker. My grandfather was a very proud, cultured man. It was with this relationship with the local union and became Milwaukee’s first full-time Black truck driver. That included snow plowing and all heavy truck operations. According to my mother, “He never was “’labor.’” Among the things that people threw away were perfectly good records: Issues of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” The works of Shelley Berman. These records, these artifacts of the midcentury, were handed down to my mother. Then I would play them. My mother would replay Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross. My father would integrate records from The Last Poets, Sun-Ra, and Sammy Davis Jr. A lot of these tastes made me weird kid. Sure, I listened to Wu-Tang and Britney Spears like the rest of my peers. But I came home to a life that was expanded by Prince, Stevie Wonder, and Led Zeppelin. This may have even made us a little iconoclastic. But we were really no different than any other Black working class family trying to make it in America.

”If you come from a working-class Black family in the midwest being cultured was a way to develop a deep and rich inner life. More than a way to define your tastes, the ways to define your humanity.

My mother often talks about how my grandmother was this expert seamstress. She, in the 1940s and 1950s, sewed the family’s winter coats and even the living room curtains. She also made homemade donuts. As a homemaker, my maternal grandmother looms large in the imaginations of my mother and I. In the go-go 1980s and 1990s my mother tried her hand at sewing, and thanks to planned obsolescence, essentially gave up after realizing a broken piece of the sewing machine was irreplaceable. Many years later into the modern millennium, I had sewn a few successful pieces. But they will never match up the legend of my grandmother. When I think about how I feel when I am cooking, baking, or sewing: the sense of self-reliance, the feeling of calm from working and reworking. I have to imagine that is what my grandmother must have felt. And in much more challenging circumstances.

Equally influential was my paternal grandmother’s much more provincial cooking taste. She was a fan of Julia Child and French cooking. She passed away during my sophomore year at Howard, while I was home for the winter break. I was beside myself. I did not even have a chance to say goodbye. I needed to find a way to stay connected to her and persevere through college. So I gathered a few of her cookbooks and brought them back with me to Washington, D.C.

”If we spent our days picking up other people’s garbage, cleaning other people’s clothes, or taking care of other people’s children, coming home to a life that was filled with Miles Davis in the air and the smell of collard greens cooking on the stove meant that we were more than what we did for a living.

I didn’t know my paternal grandfather very well. He lived through the Great Depression, but the time he retired, I knew him mostly as a man who like cigars. My parents were not particularly strict when it came to housework. In a family full of bohemians who lived in borderline chaos, my grandfather’s room was this orderly oasis. He was a military man. His bed was perfectly made every day. Every hat was in place. All of his accessories were perfectly organized on his dresser. My grandfather also grew peonies that came out every Spring. That was how I knew summer was coming. To this day, I dream of those peonies.

If you come from a working-class Black family in the midwest being cultured was a way to develop a deep and rich inner life. More than a way to define your tastes, the ways to define your humanity. If we spent our days picking up other people’s garbage, cleaning other people’s clothes, or taking care of other people’s children, coming home to a life that was filled with Miles Davis in the air and the smell of collard greens cooking on the stove meant that we were more than what we did for a living. If we sat down on a midcentury chair that was purchased at the thrift store, it was because we knew a good, well-made chair when we saw it and had the right — as a human being — to sit in one. To someone who is more visible in the mainstream, you always feel like a contemporary cutout in their life. As if you do not have this rich inner life. Or a life informed by the people who came before you. Not just a life of struggle. But a life full of self-preservation and self-actualization. We would now call it self-care.

In an era of #BlackLivesMatter when our lives are in peril, and our energy is exhausted simply trying to save our lives, our capacity to make space for joy by design isn’t just empowering. It is a reflection of our unapologetic humanity.