Nov

Black in Design @MICA

[responsivevoice_button voice=”UK English Female” buttontext=”Listen to Post”]

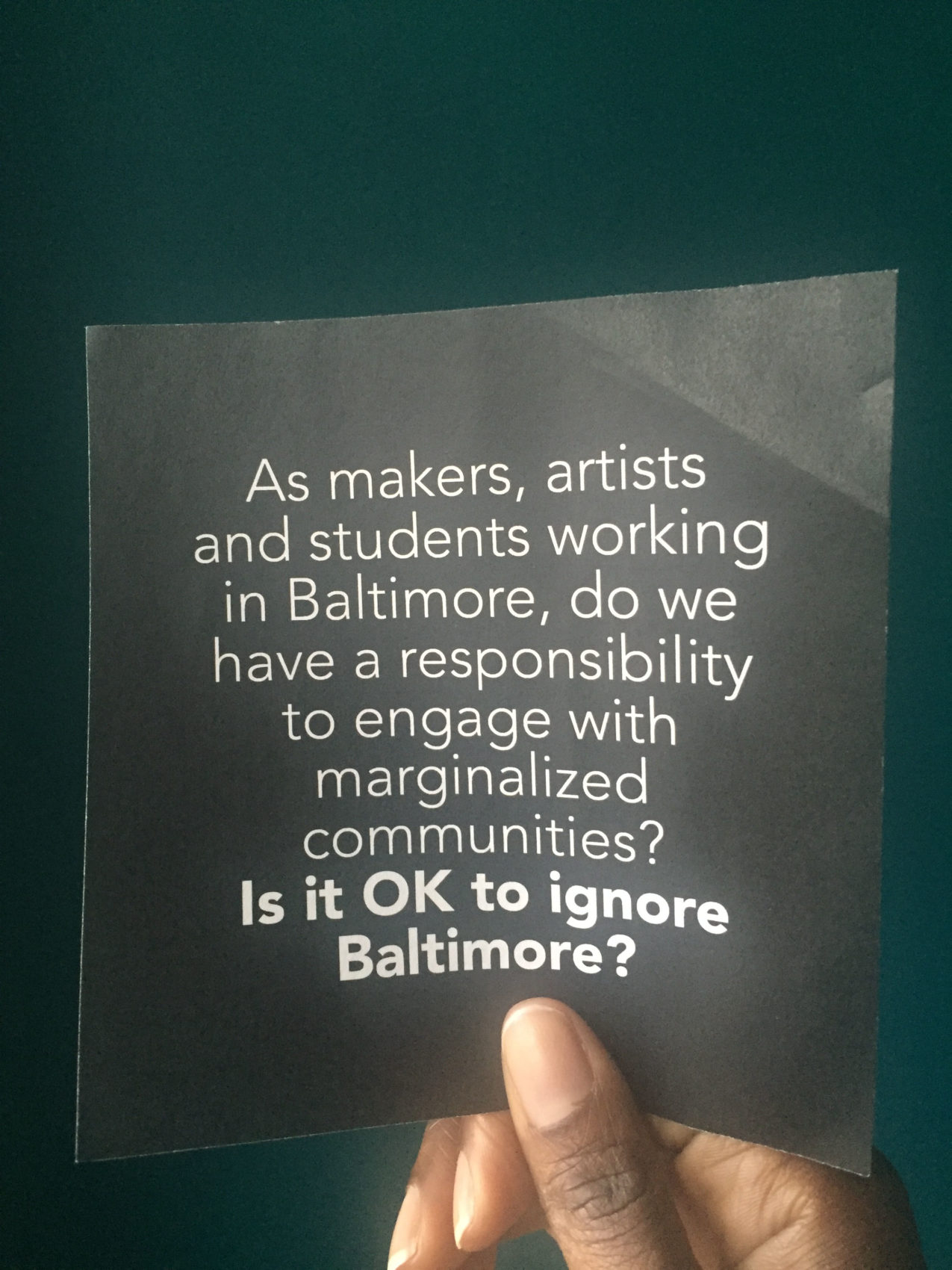

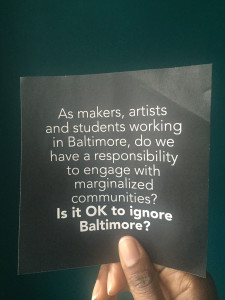

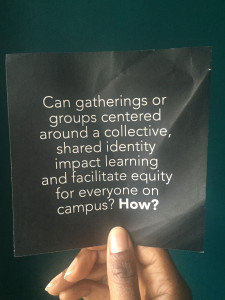

On a Fall evening in Baltimore I attended Black in Design @ MICA, a three-person panel discussion presented by students of Maryland Institute of College of Art’s (MICA) Master of Art’s in Social Design (MASD) program. After attending Harvard’s Black in Design conference this past October — and in the wake of protests against police brutality following the death of Freddie Gray — MASD students wanted to examine their experiences as students of color at predominantly white spaces. *Following a brief video presentation, six questions were presented to the audience.

During the video presentation, we were given small pieces of black paper with one of the six presentation questions printed on them.

For Black in Design @MICA, I really liked the opportunity for an open dialogue about the intersections of blackness, design, creativity, and social impact. It allowed for an eclectic mix of voices and opinions. While some understood design with a socio-political contest ( that — positively or negatively — it tells the truth) others seemed to see designers as either traditional artists or designers as simply other black professionals. I wish we had more black designers come forward and tell their stories. This lack of seeing the overlap compelled me to put in my thoughts. I mentioned that as a designer, you can stand in your own truth as a black person, and continue to privilege your creativity. I will always be black. But it takes years to develop skills necessary to thrive in this business: working in teams with different disciplines and goals; accepting criticism about your work without making it personal; determining what truly makes your creative ideas useful; refining production techniques, and so on. I will always be black. But it takes years to develop skills.

For Black in Design @MICA, I really liked the opportunity for an open dialogue about the intersections of blackness, design, creativity, and social impact. It allowed for an eclectic mix of voices and opinions. While some understood design with a socio-political contest ( that — positively or negatively — it tells the truth) others seemed to see designers as either traditional artists or designers as simply other black professionals. I wish we had more black designers come forward and tell their stories. This lack of seeing the overlap compelled me to put in my thoughts. I mentioned that as a designer, you can stand in your own truth as a black person, and continue to privilege your creativity. I will always be black. But it takes years to develop skills necessary to thrive in this business: working in teams with different disciplines and goals; accepting criticism about your work without making it personal; determining what truly makes your creative ideas useful; refining production techniques, and so on. I will always be black. But it takes years to develop skills.

”...(Design) Serves as a call to action, preserve history and culture, make the invisible visible....

Although there wasn’t a turning point when I decided to walk, there were definitely some catalytic national events that fortified my decision. Michael Brown, Darren Wilson and Ferguson. The seemingly ubiquitous police shootings and assaults on black bodies were extremely hard to take while working as a journalist. There were other journalists on the ground, covering these tragedies, writing the stories, the frustration and the heartbreaks. I was inside doing my job, and not processing in a business that is based on facts and not feelings. It is my perspective that there is not much room for personal opinions in journalism (there are reported essays, columnists and opinion writers, of course). I felt stuck not being able to say Wilson is a murderer because it was not my place in that space to say because journalists should be unbiased. Journalists should say “charged with murder,” “alleged” or other qualifying words that present the facts devoid of judgement.

However, I was always going to be a black person reading and editing and filtering the news through my head before it reached the journalist portion of my identity. This really bothered me as these kind of events kept (and keep on) happening. I am not insinuating that I couldn’t share my feelings in hushed conversations with other black or “woke” white colleagues, but it was definitely hard. I also came to the realization that our best day of news coverage is usually the worst day in someone’s life. We can move fro Pulitzer to Pulitzer award but many sources aren’t able to move on. It’s not a jab at The Post. It’s the nature of the business. I felt I was desensitized. The first time I cried about Michael Brown and so many others before and after him was months after I knew I had been accepted and was going to resign.

”To me, the real problem is not even the outright culture shock. The problem is after the shock, not moving forward and not interacting with the community, but retreating to exclusive institutional spaces as designers.

IDSL: You mentioned this phenomenon of young, typically white students enrolling at MICA, and experiencing a sort of culture shock when realizing the campus is located in the heart of an urban environment like Baltimore. Why do you think this phenomenon occurs, and do you think young designers can break out of this habit?

DJ: I don’t think habit is the right word. It’s more of a pattern that is not specific to MICA. The way I understand it is that many students — white and ethnic minorities — often look at a schools academic or curricular offerings when choosing an awesome institution. It is a no-brainer to choose the best school to give you amazing connections and credentials. However, I have observed people being overwhelmed with the pitfalls of the city when working in Baltimore. Let’s be real here. Baltimore is a very different place, with some extreme dynamics that many who are privileged to go to an art school or any private institution, have never experienced before. For the last seven years I have lived less than 40 miles away from Baltimore and I am still taken aback as I drive through the city at the economic disparity, the vacant ghost of a city that used to exist in some neighborhoods. As a black women who has lived in several cities, I am not immune to being alarmed.

To me, the real problem is not even the outright culture shock. The problem is after the shock, not moving forward and not interacting with the community, but retreating to exclusive institutional spaces as designers. At the “Black in Design: What’s Next?” event, I asked, is it “OK to ignore Baltimore?” It is not OK, but it’s easy to work isolated from city residents inside pristine university fortresses and narrow, gentrified spaces set against the backdrop of wide concentrated poverty.It is imperative that social designers, makers and innovators connect with the people for which they are designing in order to have lasting and effective interventions. Without rapport and relationships, design becomes a paternalistic prescription. What is “best” in a studio or laboratory may not even translate well without cultural literacy of the populations in need of better design for better lives.

After the initial shock, accept privilege, don’t feel pitiful “white guilt,” go beyond the bubble towards authentic community engagement. Explore and endeavor to form relationships to understand that the people who feel different or “other” are there. They are not invisible, but human with, possibly, a different set of lived experiences than students. This is obviously easier said than done for some and it is not an immediate antidote, but changing the pattern starts with mindfulness.

*I arrived shortly before the end of a video presentation, so there may have been some details missed.